The Heartbreaking Reality of Working in Immigration Law

By Melanie Torres-Godoy

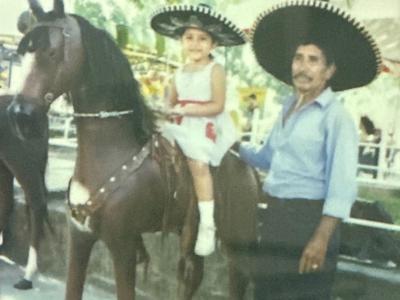

When I was five years old, my family and I packed up the few belongings we had in our beloved home country, El Salvador, and moved everything to Colorado. My brain holds select memories from my short time there: childhood friends, family, the beloved pink house where I grew up. I was too young to understand the impact this move would have on my life – or even the hardship that I had yet to face as we started our on-foot journey to the United States. My parents and I were just three of El Salvador’s citizens still affected by the ramifications of the Salvadoran Civil War, more than a decade after it ended. The lack of economic and educational opportunities ultimately led my parents to leave their lives and families behind and take our chances at living the “American Dream.”

The “American Dream”

We were not the only ones chasing this dream. Between 2000 and 2010, 13.9 million immigrants arrived in the United States, the highest number of any decade in American history, despite a large net loss of jobs during that time. Fifty-eight percent of this growth was made up of immigrants coming from Latin America. Many of them shared my story about why they decided to make the journey north: a lack of opportunities and safety for themselves and their children. Work and school are the top reasons immigrants give when asked why they made the decision to move. It is never an easy decision and one that comes with heartbreak and hardship, such as watching family members’ funerals on FaceTime to living in constant fear of being deported. A family’s decision to move to an entirely new country is one that comes out of desperation and longing for a better life.

Beyond the Media: Working in Immigration Law

I started working at the office of Claudia Villa at the beginning of 2024 with support of the CAHSS Casa de Paz Learning Community fund. While I initially helped with simple office tasks and mail at the beginning, during the summer I was finally able to work on actual cases and learn the realities of immigration law. It put into perspective the role our surrounding world and political environment had on the outcomes of many of our clients.

I mostly processed TPS (Temporary Protected Status), asylum, and juvenile visa applications. Right now, Denver has been receiving a large number of Venezuelan immigrants due to the economic struggles and political violence in their home country. Venezuelans were granted TPS in 2021, allowing incoming immigrants the opportunity to apply for deferred action and work permits. This was one of the few applications where our office received decisions in a reasonable amount of time in comparison to other cases our clients had. Even then, it is not a long-term solution – it is not residency or citizenship – and is conditional on their ability to renew every two years and whether the government continues extending TPS for Venezuela. Larger and more expensive cases, such as asylum, have an average wait time of four to six years. Applicants usually have less than a 40% chance of being granted asylum. This timeframe could be extended under an aggressive Trump administration, but that possibility remains unclear.

In June 2024, the Biden administration introduced the Parole-in-Place program, also known as “Keeping Families Together.” The program was intended to provide a path to legal status for undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens. Although marrying a U.S. citizen is considered one of the easiest ways to obtain legal status, it is a harder process for those who entered the country undetected. These immigrants are usually required to return to their home countries during the process. Undocumented individuals married to U.S. citizens may apply for an adjustment of status, but if they have an unlawful entry, they will need to complete their green card interviews in their home country. Depending on how long they have been in the United States unlawfully, a three-to-ten-year ban can be applied, unless an unlawful entry waiver is granted, which is not always the case. Many have families they cannot leave, so they continue living undocumented. Parole-in-Place would allow applicants to remain in the country while they wait for their application to be reviewed. This was a huge win for the immigrant community we served. Many clients decided to take the risk and hired us to complete the applications for them. We were excited at the prospect of many of our clients finally getting a real chance at a green card.

That excitement was short-lived. USCIS started accepting applications August 19, 2024. By the end of that week, the program was put on pause. That month, sixteen Republican-led states sued to block the program, claiming it would grant permanent resident status to immigrants who were violating federal law. On November 7, U.S. District Judge J. Campbell Barker struck down the policy. Judge Barker alleged that Congress had not given the executive branch the authority to implement such a policy. He wrote that “history and purpose confirm that defendants’ view” of the relevant immigration law “stretches legal interpretation past its breaking point.” Judge Barker was one of the judges appointed by Donald Trump during his first term in the Eastern District of Texas.

Looking Ahead

What is the “right way” to come to the United States? Does our current system make that easy, or even possible? From my own experience – as the child of a family fleeing a desperate situation - there is no right way. Every part of the immigration system is unjust and unfair. Immigrants spend thousands of dollars and years of their lives to be here legally. At the time of writing this piece, we have the results of the election. Our president for the next four years will once again be Donald Trump. Immigrants such as I know that this will not make our fight or journey any easier. The reality is that the immigration system is a system set up for failure.

The next four years will undoubtedly be a grim time for the immigrant community, and there is little many of us are able to do. Among the sea of questions and uncertainties the immigrant community will face, one thing is certain – no number of policies, laws, or walls will ever stop immigration. We must start creating a just and humane system that gives people a fair opportunity to live a safe and fulfilling life.

The morning after Election Day, I received a text from the lawyer I worked with, Claudia Villa: “it will be ok and if it is one thing I know for sure, the immigrant spirit is resilient and brave. Hold on to that. We will be ok.”

Melanie Torres-Godoy is a senior at the University of Denver studying Socio-Legal Studies and Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies. She is a Salvadoran-American with a passion for immigration, a passion that stems from her own personal lived experiences. She hopes to work in either immigration law or policy one day and create change from inside the system.